Archives

Tuesday | 02nd April 2024

blog

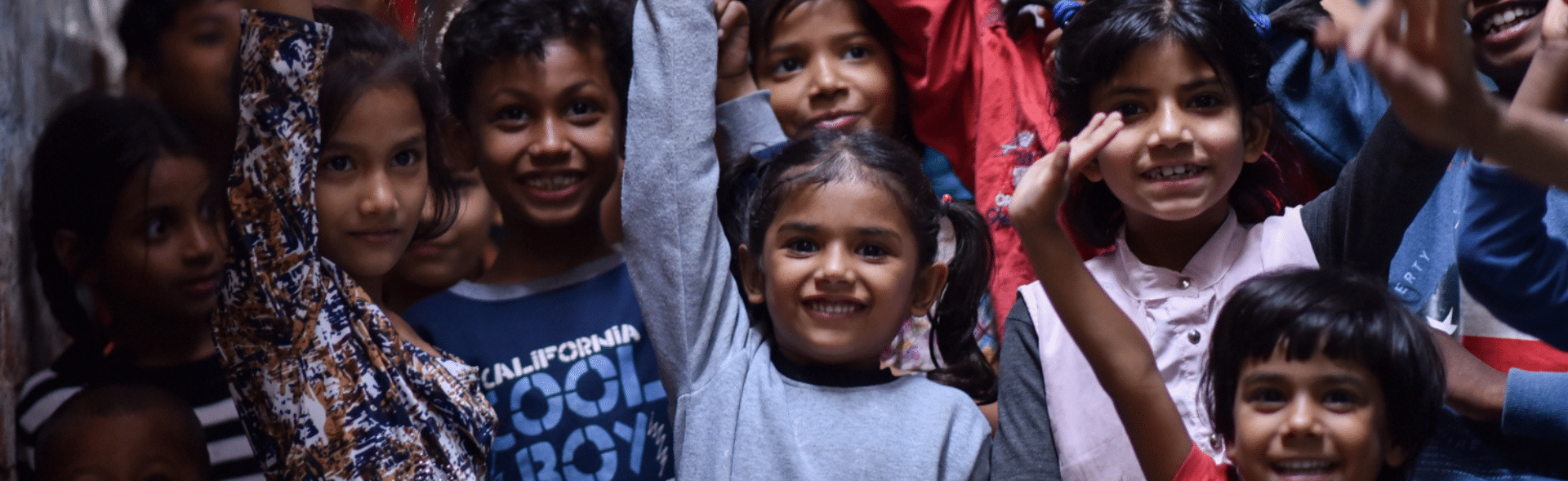

Founded in 2008, Bal Raksha Bharat (also known as Save the Children) is helping children across India enter a better…

Tuesday | 02nd April 2024

blog

The scale and speed of a disaster can be overwhelming. It is therefore reassuring that in response, India’s Disaster Relief…